25 January 2022

The stories behind the inscriptions on Australian Headstones

Often buried halfway around the world, there are many Australian servicemen and women who lost their lives during the First World War, many of whom are laid to rest in Western Europe. To mark Australia Day, CWGC’s historian Lynelle Howson discovers the stories behind the often-poignant inscriptions left by families on the headstones of their loved ones.

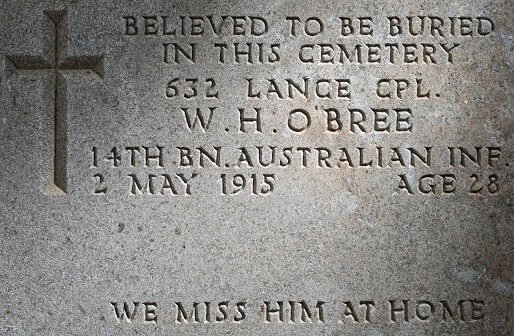

Image credit: Eric Compernolle

Over 14,000 kms from home, on the ridge high above ‘Shrapnel Valley’ and CWGC’s Beach Cemetery, in Gallipoli, is Lance Corporal William Henry O’Bree’s headstone. Born in Moulamein NSW but educated in Swan Hill VIC, he was working on his uncle’s farm near Swan Hill when war began, and he enlisted within weeks. He sailed for overseas service in December 1914, spending time in Egypt and Gallipoli.

William was killed in action on 2 May 1915. He is believed to be buried in our Courtney’s and Steele’s Post Cemetery. When his parents were offered the opportunity to choose an inscription on his headstone they said, simply, ‘We miss him at home.’

For many of us, personal inscriptions are one of the most striking and affecting things about visiting a CWGC site. While regimental badges, names, ranks and dates of death are vital and reveal interesting things, these are part of the larger story of the war – of the group, the mass, the big picture.

For the personal and human aspects, our eyes fall to the space where lines of text carefully chosen by loved ones can appear. Some, like O’Bree’s, strike to the heart and stay there. Yet, in the earliest months of the Imperial War Graves Commission’s work, designs submitted by our principle architects for a crucial item – our headstone - did not include space for a personal inscription.

One of several specimen designs, January 1918, CWGC

This space was added later on in the process - a compromise between the value of uniformity and the value of individual expression. But next of kin were informed they would have to pay per letter for the engraving of the inscription. Many who knew they could not afford the cost did not submit one. I imagine some could not find the words from a dark place of grief.

Member governments made different decisions about the issue of payment – New Zealand decreed no personal inscriptions at all, to ensure fairness, rich or poor. Australia undertook to meet the cost of those who couldn’t pay, but this was after the message had gone out about payment being required. Today, we have over 20,000 headstones for Australian service personnel of the First World War with inscriptions, in cemeteries far from their homes, from Belgium to Yemen.

French children visiting Australian graves in the Harbonnieres area, France, August 1919, AWM E05925

Walking along rows of headstones, I often notice references in Australian inscriptions to the distance between the grave of a loved one and their homes. Frequently, places in Australia are mentioned by name – farm names, small country towns, suburbs of cities, or references to Australia as a whole.

Considering that most parents and widows were writing words for graves they would never be able to visit but hoping that others would see their loved one’s headstone in their stead, perhaps they wished to underline how far their boy was from home, or to connect him somehow back to where they were – waiting for someone who would never return.

Taking one cemetery as an example, we can compare Australian inscriptions with those written for Canadians, likewise far from home. In Boulogne Eastern Cemetery in France, full of soldiers who died of wounds or disease in army hospitals nearby, there are about 200 examples of each nationality with inscriptions. Twenty-two Australian inscriptions here mention a place, 19 of these an Australian place. Fourteen Canadian inscriptions mention a place, only six of these in Canada (the others are in England, Ireland and one in the USA). One Australian inscription here tells us the family lost at least two sons – the other killed at Pozieres in the same month, August 1916; two graves they would likely never be able to visit.

Far more inscriptions mention distance more generally, rather than naming a specific town. ‘FAR AWAY FROM ALL WHO LOVED HIM IN A HERO’S GRAVE HE LIES’ is engraved on a headstone in our Heath Cemetery, Harbonnieres, France. It was chosen by the sister of George Laurie who lies beneath it. George was a stockman from Comet, Queensland, when he volunteered to join the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in November 1915.

Image left: CWGC Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, CWGC

He was an Indigenous Australian who, although discriminated against at home, volunteered to fight for Australia and the British Empire. He was accepted into the army, while his brother was refused several times for ‘not sufficient European parentage’. George reached France in November 1916. In August 1918 his battalion were in heavy fighting at Mericourt on the Somme and George was killed in action. The full contribution of Australian indigenous service personnel may never be known due to gaps in the historical war record, but today in Australia many people are working towards a better understanding of how many served, and their stories.

He was an Indigenous Australian who, although discriminated against at home, volunteered to fight for Australia and the British Empire. He was accepted into the army, while his brother was refused several times for ‘not sufficient European parentage’. George reached France in November 1916. In August 1918 his battalion were in heavy fighting at Mericourt on the Somme and George was killed in action. The full contribution of Australian indigenous service personnel may never be known due to gaps in the historical war record, but today in Australia many people are working towards a better understanding of how many served, and their stories.

Looking at inscription after inscription and taking in the heartbreak and grief behind each one, can be confronting. Some families reached for comfort through the process of selecting an inscription for their loved ones’ grave. One bereaved family in Upper Hawthorn VIC chose to quote from a letter sent home from the front: “Not lonely with the boys / I’m one of the Aussie / family here”. Today their son lies in Peronne Communal Cemetery Extension in France in a ‘family’ of over 480 other Australian servicemen.

Image right: George Laurie, State Library of Queensland

Peronne Communal Cemetery Extension, CWGC